The Rich History and Diverse Flavors of Georgian Cuisine

Georgia, one of the world’s oldest countries, is renowned for its rich culture and traditions.

Georgian wine and cuisine are among the first things that come to mind when thinking of this beautiful country.

- History of Georgian Cuisine

- Regional Features of Georgian Cuisine

- Khachapuri – The Pride of Georgian Cuisine

- Khinkali and Georgian Cuisine

- Georgian Cheese – An Integral Part of Georgian Cuisine

- Georgian Bread – Shoti / “Dedas Puri”

- Georgian Cornbread

- Georgian Sauces

- Field Pkhali and Eggplant with Walnuts – Georgian Food for Vegans

- Georgian Desserts and Sweets

History of Georgian Cuisine

Georgian culinary traditions are deeply intertwined with the country’s geographical location and historical events.

The cuisine is a result of cultural blending, influenced by various conquerors and neighbors throughout history.

Though these invasions often brought hardship, they also introduced cultural elements that were assimilated into Georgian traditions.

Eastern Georgia, influenced by its proximity to Iran (formerly Persia), has adopted some of its culinary preferences.

While Western Georgia traditionally leans toward Turkish (Ottoman) and European cuisine.

Despite these regional differences, the fundamental recipes and cooking methods remain similar across the country.

The roots of Georgian cuisine date back to ancient times, with winemaking and grain cultivation practiced since the Stone Age, forming the foundation for numerous local culinary and wine traditions.

Active trade during the Middle Ages enriched Georgian cuisine with influences from neighboring countries, introducing spices and aromatic herbs from India and Persia, along with vegetables and fruits from the Mediterranean.

Regional Features of Georgian Cuisine

A key feature of Georgian cuisine is its diverse regional variations, with each part of the country showcasing unique dishes.

Traditional dishes unique to each region of Georgia can be found throughout the country.

Some regional specialties are completely unknown even in neighboring villages. For example, “Dambalkhacho” is a traditional dish that was only prepared in Pshavi.

Other examples include Kaimagi, Borano, and Yakhni from Adjaria, which are uncommon in neighboring Guria.

In Samegrelo, the cuisine is notably diverse, featuring both very spicy and neutral dishes.

For example, Megrelians say that if Kharcho (a spicy Megrelian dish) drips onto the tablecloth, it should burn through due to its spiciness.

At the same time, they have Gebzhalia, made from squeaky fresh cheese or very fresh Sulguni.

In Meskheti-Javakheti, Apokhti is a staple, made in response to the region’s harsh and long winters.

This cold-dried meat is wrapped in gauze and hung to dry. Goose Apokhti and khinkali made from it are particularly popular, with the khinkali being smaller and more compact than usual.

Recipes for the same dishes can vary significantly from village to village and sometimes even from family to family, influenced by various factors.

Khachapuri – The Pride of Georgian Cuisine

No ritual, social, or family gathering in Georgia is complete without khachapuri.

Today, almost every corner of Georgia has its version of khachapuri. It differs in taste, types of cheese, and dough preparation techniques.

Every guest of Georgia desires to try khachapuri.

Khachapuri is more than just dough and cheese; it’s a ritual and a part of history and culture.

This is one of the most famous Georgian traditional dishes.

Each type of khachapuri has its own story. It is believed that the dish was originally an offering to the sun, which is why many are round.

However, other shapes exist: triangular, square, and boat-shaped.

For example, when they baked rectangular khachapuri Bokhchuani, they placed half a walnut kernel on each side. With this gesture, they expressed gratitude to the universe.

At Christmas, families bake Guruli khachapuri (Gurian pie) individually for each member, reserving the largest for the head of the family.

They prepare smaller pies for children and a special large one, packed with the most eggs, for the centerpiece.

Traditionally, they place this pie at the center of the table and light a candle on top, symbolizing the family’s abundance and wealth.

Shaped like a crescent moon, the pie and its egg filling represent fertility, a good harvest, and prosperity.

List of the Most Popular Khachapuri

Imeretian Khachapuri

Also called Ketsi Khachapuri, this version uses a clay pan called ketsi and bakes on hot coals in the fireplace. Villagers in Imereti still follow this tradition today.

Georgians judge the best Imeretian Khachapuri by specific criteria: the dough must be thin and tender, and the cheese must be Imeretian—slightly salty, squeaky, and sufficiently fatty.

Megrelian Khachapuri

Megrelian Khachapuri uses two varieties of cheese. There are its old and new recipes.

The dough for Megrelian khachapuri was once only kneaded with milk or the whey left after making cheese, along with a little bit of salt and oil.

Sourdough was used as leaven, and the dough was supposed to be unquestionably soft.

The modern type of Megrelian Khachapuri has become more convenient.

Now the cheese is put into the dough, closed, and flattened evenly, with cheese (usually Sulguni) mixed with egg spread over the top, then put into the oven and baked on high heat. Top it off with a dollop of butter.

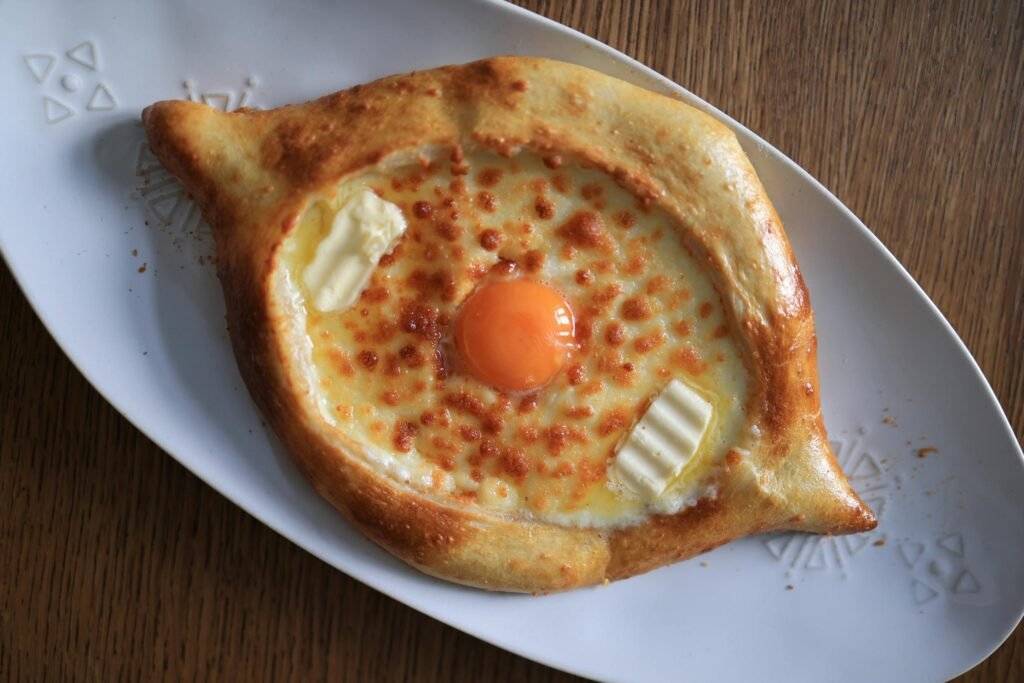

Adjarian Khachapuri

Adjarian Khachapuri stands out with its unique shape and exceptional flavor.

While classic Khachapuri can be served with other dishes, Adjarian Khachapuri is best enjoyed on its own as it’s a very filling dish.

There are many versions of how Adjarian Khachapuri was created.

The Laz people living by the sea gave the dough the shape of a boat, and the egg yolk seems to symbolize the sunset on the sea.

The dish can be eaten both ways – with your hands or with a knife and fork.

The main thing is that it is hot. The hot cheese, egg yolk, and butter placed in it should be mixed well so as not to break the shape of the boat and not spill the filling.

Khinkali and Georgian Cuisine

It’s impossible to visit Georgia and not try khinkali. It’s a masterpiece of Georgian cuisine and an integral part of the country’s culture.

In the mountainous part of Georgia, it was considered a symbolic dish offered to the sun and was typically prepared on Sundays and holidays.

There are several stories about the origin of khinkali.

According to one of them, this is the story of Khevisberi, a secular and ecclesiastical ruler of Khevi in the Eastern Georgian highlands, and his wife Khinda.

In honor of their guest, Khinda specially prepared a delicious meat dish. The food was so tasty that it was named after her – “Khindali,” which eventually evolved into “Khinkali”.

According to the second version, it was called “lkhinkari” (“feast door” in Georgian), since it was prepared for a celebration and was a dish offered to the sun.

In Georgia, you can try Khinkali prepared with cottage cheese, goose Apokhti, cheese, potatoes, and mushrooms, as well as modernized versions of it, for example, with shrimp.

Georgian Cheese – An Integral Part of Georgian Cuisine

Cheese is an indispensable product of the daily menu in Georgia. There are many recipes for cheese dishes in the Georgian gastronomic culture.

The cheese found in Georgia is eight thousand years old.

There are many types of Georgian cheeses, but during the Soviet period, the methods of producing Georgian cheese were lost, which can be considered the fault of the Soviet economy and politics.

In recent years, researchers have been actively studying the history of Georgian cheese, as a result of which many types of its production have been found and restored.

Rennet

Rennet is a special liquid or powder necessary for extracting high-quality cheese.

People use various traditional methods to prepare rennet, which goes by different names across regions.

In mountainous areas, they call it ‘cheese medicine,’ while in Kartli and Kakheti, it is known as ‘Machiki,’ ‘the mother of cheese,’ or ‘Dvrita.’

Creating natural peasant cheese is a time-consuming process that requires good cattle, pastures, environment, and human resources.

Imeretian Cheese

Imeretian Cheese is a prime example of Georgian cuisine.

It complements any dish, especially Mchadi – Georgian cornbread.

Imeretian khachapuri is unimaginable without it.

Imeretian cheese is part of the raw cheese group, is made by hand, and is also called “hand” cheese.

It is primarily produced in the Imereti region.

Tushetian Guda Cheese

Guda cheese has been honored as part of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Georgia.

Due to its distinctive flavor and ancient production techniques, it is one of Georgia’s exceptional cheeses.

Tushetian guda cheese uses fresh, whole sheep’s milk or a mix of sheep and cow’s milk.

Cheesemakers ripen the milk in a sheepskin bag (“guda” means bag in Georgian) with the hair facing inward.

They place four or five cheeses in the bag, layering salt between them, tie it up, and store it in a cheese room under a towel for two days.

To ensure the cheese absorbs the salt, they turn it over several times a day, which changes its shape. The cheese then ripens in the bag for 60 days.

Sulguni

Megrelians and Svans are considered the first producers of Sulguni.

This cheese is made from fresh milk from a cow or a buffalo.

Sulguni is very tasty both as a standalone dish and is widely used for making khachapuri, gebzhalia, and nadugi (a type of cottage cheese).

If you prefer your Sulguni to be fresh and less salty, then you can get the soft kind, which is milky and tastes more acidic.

If you like it to be saltier and more well-aged, then you should choose the dry kind, which is the best with Megrelian Ghomi.

It also goes well with soft, freshly kneaded Elarji, khachapuri, and Megrelian Chvishtari.

Tenili Cheese

“Meskhetian Tenili” is a unique and special type of Georgian cheese and is included in the list of intangible cultural heritage of Georgia.

Tenili cheese can be made from sheep or cow milk and is known for its high-fat content.

The cheese is rolled in warm whey until it forms strings. After that, it is washed in cold saltwater, hung out to dry for a day, then cut, dipped in cream, and packed into an airtight clay pot.

The name Tenili comes from the Georgian word “tenili,” which means “packed.”

Dambalkhacho

Dambalkhacho is a type of blue cheese that has been made in the mountains for as long as anyone can remember.

This unique product is crafted in Tianeti and Pshavi, Georgia.

Dambalkhacho has a moldy exterior, but inside it is soft and golden. It can be enjoyed both dried and fried in a pan with plenty of clarified butter.

It is similar to the world-famous fondue.

Adjarian Chlechili

The cheese has a thread-like or braided form.

The threads are dense and quite hard when stretched.

Adjarian Chlechili differs from other twisted cheeses due to its unique production and maturation process, resulting in a characteristic taste and consistency.

It is prepared on summer pastures located at an altitude of 1800-3000 meters above sea level. The milk produced in these healthy natural conditions ensures the high quality of the cheese.

Georgian Bread – Shoti / “Dedas Puri”

Bread is the primary food product in Georgia.

Many historians document the production of various types of porridge and bakery products from grain and cereal in Georgia.

In ancient times, bread was used as a form of alms, as well as a provision for soldiers marching off to war.

Shoti, also known as ‘dedas puri’ or ‘mother’s bread,’ holds a special place of importance in Georgia, a country known for its abundance of bread varieties.

Shoti has its origins in Kakheti, where it was traditionally baked in a tone oven by women, particularly the eldest mother of the family.

When baking shoti, the flour is carefully chosen, as the taste of Georgian peasant bread is defined by the wheat and how it is milled.

The wheat used to be milled in watermills in villages, which gave the flour a unique flavor.

The tone oven is crucial for baking shoti bread. It is a cylindrical structure made of terracotta with no base that is dug into the ground.

The tone must be heated well before baking the bread.

Kakhetian shoti is often compared to a sword (khmali), which is why it is also affectionately called ‘khmala.’ It is long and crescent-shaped, thick on one side and thin on the other, and pointed at both ends.

Traditionally, shoti bread is not cut. Instead, the loaves are arranged in the center of the table to create a certain look.

Georgian Cornbread

Corn was first introduced to Georgia in the 17th century and quickly became a widespread crop, competing with and almost completely replacing earlier crops such as millet.

Mchadi

Mchadi is a traditional Georgian cornbread that can be found both on restaurant menus and on family tables throughout the country.

It is made by kneading together water and corn flour.

Mchadi can be made in various ways, but the results are equally delicious.

One method involves using a stone pan. Another variety is ‘ketsi mchadi’ (mchadi cooked in small clay pans), and baking mchadi in a ghadari (fireplace) is another popular method.

The key to making good mchadi is the quality of the flour. The dough should be kneaded with warm water and a small amount of salt.

There’s an old saying that mchadi should be kneaded for so long that it almost bakes in your hands.

Chvishtari

Chvishtari is a pastry made by baking a mixture of Georgian cheese and corn flour.

It is originally from the western regions of Georgia, specifically Samegrelo and Svaneti.

We can consider Svanetian Chishdvari as the precursor of Chvishtari. It was made not from corn flour, but solely from black millet.

Ghomi

Ghomi is an ancient, traditional dish from Samegrelo.

It is an ancient type of millet that was widespread in the lowlands of western Georgia, around Samegrelo and Guria.

In Samegrelo, making ghomi was a complete ritual. The lady of the house would comb her hair, shake the dust out of her clothes, put on a white headscarf, and start washing the corn flour.

The first water of the corn flour would be full of ghomi milk, so it would be passed through a special sieve to be poured and boiled without the ghomi losing its flavor.

Corn flour was washed with running water until clear. It was supposed to be completely white.

So corn flour made by a good housewife would not have a single dark spot, and the ghomi would come out bright white.

Usually, more ghomi would be made than necessary for all family members so that there would be enough to serve any guests as well.

Georgian Sauces

Ajika

Ajika is far more than just a seasoning; this extraordinary spice mix can completely transform the flavor of any dish.

It has been immensely popular in the Samurzakano-Apkhazeti area (western Georgia) for centuries.

Translated from Abkhazian, ajika means salt. It was originally called apiripil djika, or pepper salt, and traditionally consisted of only red hot pepper and salt.

The paste-like spicy ajika is a blend of dried spices with the addition of garlic.

Depending on the ingredients used, it can come in different colors—red, green, yellowish, and even white.

In modern Georgian cuisine, ajika is made with a wide array of ingredients, including feijoa, persimmon, and even kiwi.

Ajika has evolved into a sauce, paste, and even an incredible aperitif, and is readily available for purchase everywhere.

Tkemali

Tkemali is a sauce with traditional Georgian spices made from cherry plums, alucha (Prunus vachuschtii), or fresh plums. It is the most popular sauce in the country, and you will hardly find a family that does not make it.

The sauce has a sour taste and is typically green or red. In addition to fruits, its main ingredients are hot pepper, salt, garlic, dill, coriander, and pennyroyal.

Bazhe

Bazhe is a staple at many Georgian supras, especially during holidays and New Year’s celebrations.

It has become an integral part of Georgian holiday traditions.

Originally from Samegrelo, Guria, and Imereti, bazhe has now found its way into restaurants and family kitchens across Georgia.

There are now many variations of bazhe, but one essential requirement remains constant: using the finest quality walnuts and spices.

Traditionally, bazhe is paired with fried chicken. Although some chefs also recommend serving it with boiled meat, squash, cauliflower, and eggplant.

Field Pkhali and Eggplant with Walnuts – Georgian Food for Vegans

Pkhali

Pkhali is a distinctive Georgian dish made from a green herb mixture combined with walnuts.

This type of dish is quite rare globally.

While pkhali is prepared in various regions across Georgia, it is most commonly associated with Imereti.

This dish often incorporates more than nine different healing herbs, with nettles and amaranths being essential.

Other key ingredients include mallow, goosefoot, bugloss, shepherd’s purse, primrose, violet leaves, and woundwort.

Many cooks also add garlic leaves and stems, vine buds, beetroot leaves, fresh Welsh onions, and purslane.

The combination of these diverse plants reveals the rich traditions of Georgian cuisine, which is deeply rooted in plant cultivation and brimming with secrets.

While these herbs continue to be used therapeutically in phytotherapy worldwide, the ancestors of Georgians turned them into culinary delights.

Field pkhali is a dish that highlights Georgian cuisine’s reputation for being exceptionally ecological, healthy, and authentic.

Eggplant with Walnuts

Eggplant with walnuts features two primary ingredients: eggplant and walnuts.

The true secret lies in the precise use of seasoning and the techniques employed by both home cooks and professional chefs.

This eggplant dish is classified as a salad and represents a notable “achievement” of Western Georgian cuisine, particularly Imeretian cuisine. Today, it is prepared in various ways across different regions.

Georgian Desserts and Sweets

We are unlikely to find another country where walnuts are used in such large quantities as in Georgian cuisine.

It is not surprising that they are used abundantly in Georgian desserts and sweets along with wine.

Pelamushi

Pelamushi is a traditional Georgian delicacy whose origins at Georgian supras remain a mystery.

It is made from two main ingredients – grape juice and corn flour.

For pelamushi to maintain its status as a natural product, no sugar can be added during its preparation.

Once you’ve tasted this delightful treat, you’ll understand why! The natural sweetness of the grapes is more than sufficient.

Housewives intentionally keep grapes in the vineyard or on the pergola until late fall, sometimes as late as October or November, to ensure the bunches have fully ripened in the sun and reached their maximum sweetness.

A good pelamushi requires good grapes to be processed properly, and then the juice to be poured into a thick-bottomed saucepan.

One liter of grape juice is added to one glass of corn flour and mixed well with a wooden spoon. The flour should be completely dissolved, and stirring is continued until the thickened juice boils.

Tatara

Like pelamushi, tatara uses grape juice as a main ingredient, but it requires wheat flour for its preparation.

The exact origins of the term ‘tatara’ remain unclear.

Archaeologists in Georgia have discovered evidence suggesting that people dipped churchkhela into this concentrated grape juice as early as the 2nd century CE.

They found clay tablets during excavations, along with a unique clay container ancient Georgians used to store churchkhela.

Tatara is a traditional dessert from Kakheti, typically served during joyful occasions.

To prepare tatara, cooks gently heat badagi (sweet grape juice called tkbili) in a pot. They add one cup (about 200 grams) of gray or white flour per liter of tkbili, stirring until it fully dissolves.

It’s crucial to stir the mixture constantly to prevent the flour from clumping or sticking to the bottom of the pot.

As the mixture heats, it gradually becomes sticky and thickens. The boiling process is complete when the flour’s raw smell has disappeared.

Once done, the tatara is spread onto a plate, lightly sprinkled with finely chopped walnuts or hazelnuts, and allowed to set.

Some people prefer to add the nuts while the tatara is still boiling, while others pour the finished product into molds to create various shapes.

Churchkhela and Janjukha

Georgian warriors carried churchkhela on their journeys because it satisfied hunger and stayed fresh for long periods without special preservation.

Archaeologists have uncovered clay vessels used to store churchkhela and confirmed their purpose through chemical analyses.

This evidence shows that Georgians have been making churchkhela since ancient times.

Churchkhela consists of nuts strung together and repeatedly dipped in tatara.

The most renowned variety is Kakhetian churchkhela, which features halves of walnut kernels inside.

Western Georgians enjoy a similar dessert called janjukha.

In the Guria, Samegrelo, and Imereti regions, people use hazelnuts more often than walnuts. They add corn flour to the condensed juice instead of wheat flour.

Some regions also include dried fruits, apricots, and pumpkin seeds as fillings.

Gozinaki

In Georgia, New Year celebrations are inconceivable without gozinaki. The most ancient versions of this treat can be traced back to the mountainous regions of the country.

Gozinaki is made from just two main ingredients—honey and walnuts—though a touch of sugar is also added.

While the preparation is relatively simple, each family has its own unique recipe.

Traditionally, gozinaki is made by the family member who is most skilled in its preparation.

Conclusion

From khachapuri to desserts, Georgian dishes not only showcase the country’s rich culinary heritage but also offer inclusive options that celebrate a variety of dietary preferences.

Whether you’re indulging in traditional sweets or exploring regional specialties, Georgian cuisine provides a welcoming experience for all.

The main advantage of Georgian cuisine is its ability to cater to a diverse range of tastes. It appeals to gourmets, adherents of various religions, vegetarians, and vegans alike, ensuring that everyone can enjoy its flavors.